Jonathan Ullyot

A drawing is a little fragment of the full or “master” diagram: a discarded cutaway of an imagined more complex whole.

The content works only as a trigger: the crucifixion, the grid, the serial killer. The content is mythos: relating to myth, but also, a set of assumptions about something that is usually wrong.

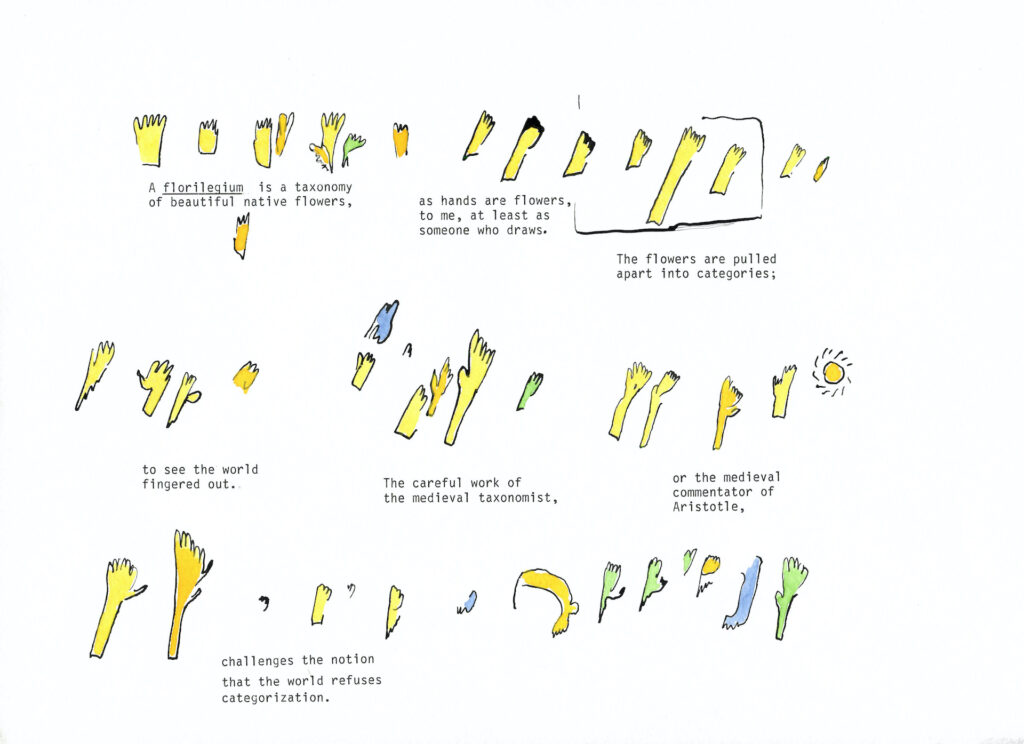

The index or florilegium contains the whole universe in a book. Index drawings are the visual equivalent to the written index of the universe. The goal is to index everything that can be drawn.

But the goal is also to fail. In failing to find anything but the fragment, one exhausts the possible (including hope) and rediscovers home.

Failures include:

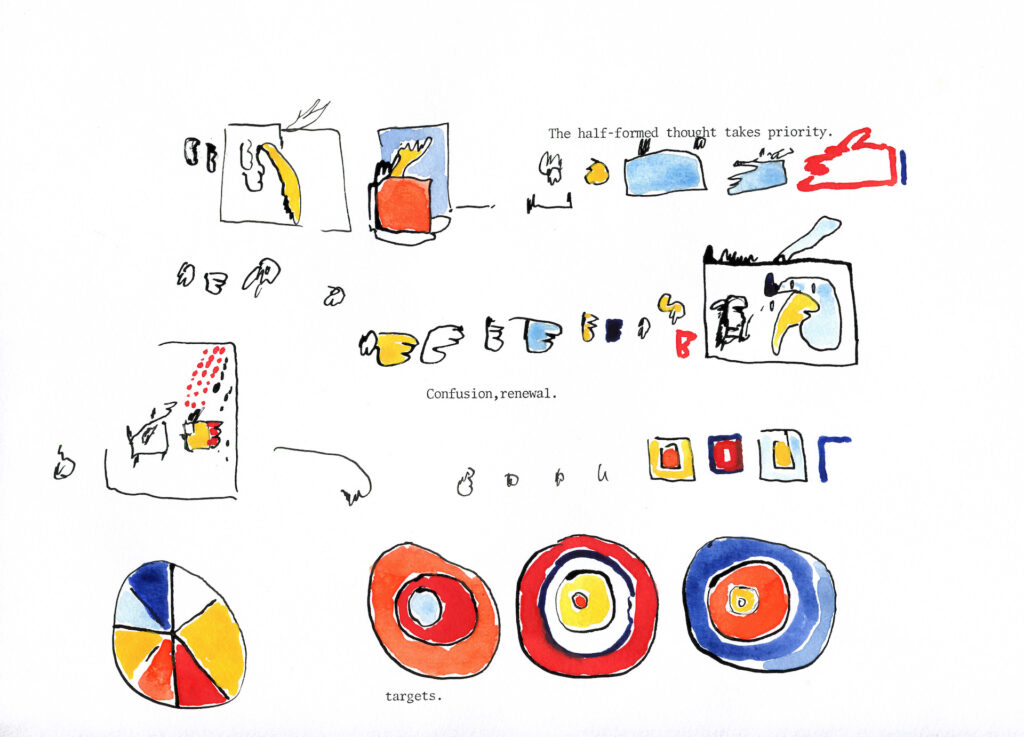

failed pictorial languages: non-communicative; notes toward an impossible language; like if Linear A was a mystery even to the Cretans

failed indexes: incomplete

failed grids: grids that fail not to be uniform but to really transform into anything aesthetic

failed information: like an anti-smoking poster, or a map, or What To Do If Someone Is Choking

One example:

You come across an old map in a dusty book at a university book sale; it’s part of some dissertation on geology written in 1942. You buy the book because it seems special. Also it’s only $2. The topic is not special: but everything else is: the numbers and the charts and the strange old map of some piece of land no one cares about anymore. You cut the map out of the book and tape it to your wall while you write a final paper about Oedipus and Nietzsche on an IBM PS/1. This map represents your escape; your release; your true self. It seems like it should be worshiped.

In other words:

art is personal, but a person isn’t much of anything

art is “found” like language and thought are “found”: they provide the illusion of originality but they are just systems through which we speak that we didn’t invent (and, like original sin, creates guilt, or evidence of past lives, or childhood abuse, etc.)

“imagination” is just a brief moment of gazing outside of language and seeing a dead cold world

art reveals the human secret: that we don’t belong on this earth; and it’s high time we prepared to leave.

One more example:

A man drives up to do some fishing on Lake Winnipeg. He buys a bottle of Crown Royal at the Liquor Mart in Beausejour. He fishes all day on Chalet Beach drinking whiskey and coke. Walking back along the path to his car, he realizes that he’s lost his car keys. So he wanders back and forth along the path asking anyone else if they’ve seen his keys. One guy idling on the beach in a 1998 Grand Prix asks him if he wants to get high.

In the morning, the man wakes up missing his wallet and his car. He decides to walk home. Only he gets all turned around and heads north. After a long day of wandering, he meets another guy in trailer who claims to be Samuel Taylor Coleridge. They drink a twelve pack of Keystone Light and have a fire.

The next morning, the man is convinced that he’s killed someone: specifically, a girl and her little white dog. He resolves to never return home. That’s when he starts to think about images. The trail of ants or the shape of moss. Now he’s a Canadian visual artist, with no meaningful precedents or role models.

Eleven months later he dies near the Bloodvein River with a backpack full of drawings. Some of them suggest he was on a quest to find the mythical staircase near York Factory that leads to the Overworld. Others detail an assault on the Bisset Gold mine. Others attempt to decode the Tie Creek Petroforms. His work is a powerful tool to maintain the spirit of Old French aventure: happenstance as fate and communication with God.